13 minutes

Engage organization-wide through digital visioning, pilots and learning.

In January 2020, a consulting client—we’ll refer to them here as Major Metropolitan Credit Union—was coming off one of its most successful years ever. Member satisfaction scores had climbed to an all-time high. Profitability measures pointed to impressive financial strength. Ambitious plans to build new branches were forging ahead. Within a few short weeks, however, a deadly microscopic virus arrived and changed everything. Sick patients overwhelmed local hospitals, businesses shuttered their doors, and MMCU was thrust into an existential crisis.

Yet the COVID-19 crisis created opportunities for renewal as well. The pandemic accelerated changes already taking place in the CU’s workplace culture. Throughout 2020, we documented the transformation to capture the ways that staff were improvising—sometimes in ways that suggested valuable new paths for going forward. We also created forums with leadership and front-line staff to reflect on these pathways. These discussions ultimately created an opening to introduce the notion of “digital transformation” as a means of building on the momentum of the newly emergent ways of working.

MMCU responded well to the crisis. Work that the CU’s leaders and staff had done on breaking down silos and collaborating across departments made them more resilient as they transitioned to remote work. Their cooperative values also kept morale high. In contrast to big banks that reacted to the pandemic by slashing jobs, closing branches and forcing customers online, MMCU supported employees taking COVID-19 leave, opened a new branch and utilized its skip-a-pay program to assist members with delinquent auto and home loans. Meanwhile, branch employees stepped in to assist overwhelmed contact center agents who were flooded with phone calls. However, while MMCU was resilient, its leaders realized that they could be more resilient if their digital tools were more effective.

We build on our work with MMCU to discuss how credit unions can engage organizationally with digital transformation. For most people, digital transformation conjures ideas of the latest technology: mobile devices, cloud computing, artificial intelligence, blockchain. Yet while technology plays an important role in digital transformation efforts, we discuss how credit unions can lay the groundwork organizationally for successful digital change efforts. Specifically, we explore ways, including visioning and pilot projects, in which credit unions can connect the adoption of digital technologies with specific organizational needs. We also discuss how credit unions can create the right cultural environment and promote receptivity to digital change by creating learning organizations.

Crafting a Digital Vision

“We need to have a shared vision and digital roadmap!” exclaimed MMCU’s CEO a year into the pandemic. Through crafting an organization-wide digital vision, the CEO hoped to ensure that the objectives of the business units aligned with the overarching digital strategy. At that point, a number of pilot teams were already knee-deep in digital transformation work. These efforts focused on things like enhancing online collaboration, augmenting digital product training, working out the kinks in the member service request system, and streamlining MMCU’s ever-expanding ecosystem of internal systems and applications. But these digital change efforts lacked a clear North Star. In this context, MMCU’s leadership sought clarity about the digital vision to ensure that the pilot teams were rowing in the right direction.

In their book, Lead from the Future: How to Turn Visionary Thinking into Breakthrough Growth, futurists Mark Johnson and Josh Suskewicz describe one way to arrive at a compelling future vision. But before engaging in futuring, they lay out a caveat: that leaders should be wary of what Johnson and Suskewicz call the “present forward fallacy.” This is the idea that organizations can simply extend their current way of doing things into the future through incremental improvements.

Blackberry learned the limits of that approach on Jan. 7, 2007. That was the day that Steve Jobs unveiled the first Apple iPhone—an iPod, phone and internet communicator in a single touchscreen device. Research in Motion’s decision to ignore Apple’s threat and continue incrementally improving the Blackberry led to its loss of the handset war by 2013.

The story of Blackberry is the reason Johnson and Suskewicz urge leaders to extend their visioning horizon to a distant future and then work backward to the present. To be exact, they suggest looking five to seven years out, where the horizon appears fuzzy, like an impressionist painting. To identify that future, they challenge leaders to identify key “inflection points” in their industry. In the automotive industry, they point to autonomous vehicles. A world dominated by driverless cars would not only make car ownership obsolete, but also see auto insurance rates plummet, ride-sharing fleets boom and auto manufacturers cede ground to tech companies like Google and Apple.

Following Johnson and Suskewicz’s lead, we embarked on a round of discovery-driven interviewing, encompassing MMCU’s entire leadership team, key board members and a swath of visionary consultants. In driving those conversations, we sought answers to a set of core questions: What disruptive technologies could significantly change the cost-value equation of the financial services industry? How might these technologies impact the way that MMCU conducts its business? What type of financial problems might MMCU’s members be trying to solve in 2030? How could MMCU help solve these problems? How might MMCU’s working environment shift in response to changing markets and member needs?

Through these in-depth, multifaceted conversations, a key disruptor surged to the top: embedded finance. In their recent book, Embedded Finance: When Payments Become an Experience, fintech thought leaders Scarlett Sieber and Sophie Guibaud distill the essence of embedded finance: Your money appears instantly and transparently in any context. Whether making a purchase with a smartphone in the grocery store, opting for buy now, pay later at the point of sale, or tipping an Uber driver through the Uber app, payments are made naturally and invisibly at the point of context.

Steve Williams, president of CUESolutions provider Cornerstone Advisors, Scottsdale, Arizona, further clarified the challenge of embedded finance, noting how it had crossed the moat that formerly protected the banking and credit union industries. By breaking down the financial services that banks and credit unions offer into their component services or “use cases” (e.g., making a payment, transferring money, borrowing money), fintechs have succeeded in embedding commerce anywhere. Examples might include Starbucks making it possible for customers to pay using a stored value card or Amazon allowing small-business owners to borrow money against their receivables.

In our work with MMCU, we captured the essence of this and other disruptive threats. We then facilitated a discussion with the leadership about how MMCU’s business model might morph in response to these threats. From the conversation, it became clear that MMCU needed to continue to rely on easy payment and money transfer solutions like Zelle and Transfer Now.

Given its size, MMCU also needed to partner strategically with fintechs that could help in areas like digital onboarding, loan origination and identify verification. To forge such partnerships, MMCU also needed to leverage its custom-coding capabilities to gain access to real-time data, eliminate data silos and leverage the benefits of data analytics driven by artificial intelligence.

Each of these future directions were part of the foundation for MMCU’s vision statement. As Johnson and Suskewicz note, a good vision statement should be more than a generic phrase or two. In fact, it should tell a succinct story in a couple of paragraphs about what the future will hold, what it means for your organization and how your organization will shape the future.

Johnson and Suskewicz also challenge organizations to consider new growth opportunities that might leverage core capabilities but in new and distinct businesses, with new business models. MMCU, for instance, explored the idea of expanding its reach in small-business lending. The CU’s leaders also discussed pursuing a partnership with a fintech to help develop a suite of small business products. They then incorporated these ideas into their vision statement. In the end, the vision told the “what” and “why” of where they were headed and how they planned to get there.

Digital Barriers and Breakthroughs

Our actual digital visioning work with MMCU began in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. The rapid transition from on-premises to remote work forced MMCU’s employees to adopt, literally overnight, several new ways of working. To document those changes, we conducted a study of the barriers and breakthroughs in MMCU’s workplace culture in response to the pandemic. Through interviews with leadership as well as front-line and back-office staff and with the support of a group of “culture journalists” who helped to document changing work practices, we discovered a number of breakthroughs that had important ramifications for MMCU’s digital future.

First, the rapid shift to remote work didn’t significantly impact overall productivity. One self-described “super commuter” who formerly left at 4:45 a.m. to avoid a two- to three-hour morning rush-hour commute found it easier to focus while working from home. A call center manager similarly described how his hybrid work schedule gave him greater flexibility to organize his workday in ways that increased productivity. He could work his normal shift during the day, but if anything was left over, he could quickly log into the office in the evening after he had put his children to bed. Not having to physically be on-site to do his work enabled him to stay ahead of the curve, making his mornings more relaxed. With the shift to virtual meetings, back-office staff similarly discovered that they could attend weekly branch meetings via Zoom without having to travel long distances to the branches.

In addition to remote work, employees made other productivity gains by inventing new digital work processes for transactions that had previously required paper documentation. For instance, they developed a remote process for wire transfers that facilitated easy audit, file sharing and approvals using digital signatures, effectively streamlining workflows. Remote work also contributed to heightened contact among departments, which switched from quarterly meetings to short, daily morning check-ins on Zoom. Other employees developed a new content management system with remote folders for sharing documents online. And MMCU’s chief information security officer used the pandemic as an opportunity to accelerate the CU’s cloud migration plan so employees could connect to the credit union from anywhere.

Rather than treat the pandemic as a crisis, MMCU turned it into an opportunity. By documenting the many types of innovative practices taking place spontaneously with the transition to remote work, MMCU attempted to capture and codify these changes, then communicate them to the rest of the organization.

Enacting Digital Change

MMCU’s research into COVID-19’s impact on its workplace culture, coupled with a virtual town hall, led the leadership to focus its organizational change efforts on digital transformation. It formed a series of pilot projects to address troublesome operational issues that might benefit from digital change.

Harvard Business School Professor Amy Edmondson refers to such pilot teams as a critical ingredient to forming what she calls a “learning organization.” She urges organizations to use pilot teams to promote active processes of research and data gathering on operational issues, customers and technology trends. But to create such teams, she suggests that leaders commit time and resources to problem identification, active reflection and knowledge transfer. She also advocates creating what she calls “psychological safety” in organizations so that employees can express their viewpoints freely, report mistakes and try out new ways of doing things.

In the aftermath of the pandemic, MMCU embraced pilot research teams as a way to further the momentum of workplace changes ushered in by COVID-19. As previously noted, these pilot projects focused on four troublesome operational issues. They included improving MMCU employees’ ability to communicate about its digital product and service offerings, enhancing the quality of cloud-based collaboration tools for employees, augmenting MMCU’s member service request system, and streamlining the 130-plus systems and applications so that they were easier to access and navigate. Not each of these issues necessarily focused on big, earth-shattering, digital company makeovers. But they didn’t need to.

Learning Organizations

Columbia Professor Rita McGrath, in an article entitled “Discovery-Driven Digital Transformation”, recommends that organizations begin their journeys of digital change by focusing on operational issues that pose challenges or require cumbersome workarounds. She suggests that these are areas that digitization can likely improve. In our experience, they can also point the way towards further areas for digital technology adoption, leading to a kind of virtuous circle.

McGrath suggests that teams conduct research on the troublesome processes, then look for ways in which to redesign these processes so that technology adds value. Once teams have identified the problem areas, studied the causes of the problems and proposed solutions, she further recommends that they identify metrics to measure their progress. By starting small with a portfolio of experimental projects and demonstrating financial or productivity impacts, McGrath maintains that organizations can learn their way into a digital strategy.

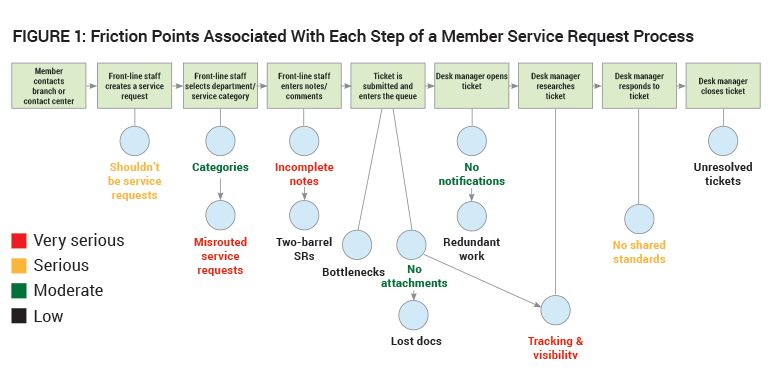

This is exactly the path that MMCU pursued with its member service request and other pilot projects. In the case of the service request pilot, its pilot team conducted in-depth interviews with front-line staff as well as the service request desk managers in every department. The interviews focused on each employee’s perspective on the steps involved in the life cycle of a typical service request and the associated friction points. We then worked with the pilot team to create a process map showing the relationship between the various steps and the breakdowns or “friction points” associated with each step. (See Figure 1 above.) The process map helped give visibility to the relationships between the steps and the various friction points.

The pilot team members then organized a workshop with the desk managers using the process map as a communication tool to discuss ways to address the friction points. The friction points labeled in red and yellow received particular attention since they were most frequently mentioned in the interviews.

The process map showed, for instance, that front-line staff frequently initiated member service requests for issues that they could have resolved directly with the proper training. Similarly, back-office departments created too many service request categories for front-office staff to easily manage, resulting in misrouted service requests. The failure of front-line staff to provide detailed information in the notes section of service requests similarly resulted in a lot of back-and-forth email traffic.

By the end of workshop, the desk managers identified resolutions for each of the friction points. They also agreed on a set of standard response times for each type of service request.

By organizing a twice-annual virtual town hall, in which research participants shared their findings, MMCU also drew other employees into the energy of the incipient digital changes taking place in its workplace, promoting dialogue and reflexivity. CUs can foster such reflexivity by nurturing applied research within organizations and fostering dialogue about it. Not only do such venues for dialogue improve employee engagement, they also promote new lines of research and help organizations foster organizational change.

Incremental Approach

While digital transformation might seem daunting, taking an incremental approach focused on leveraging pilot teams, organizational learning and digital visioning provides a promising pathway.

To be sure, credit unions with limited resources can begin a digital transformation by becoming learning organizations and looking at the operational workarounds that might benefit from digital technologies. Once they’ve rolled up their sleeves with pilot projects, a robust digital visioning process can shed light on strategic opportunities related to cloud solutions and fintech partnerships. Using digital tools to gain operational efficiencies and better serve member needs can not only help CUs survive but thrive in the era of the new digital economy. cues icon

Matthew J. Hill, Ph.D., is an organizational anthropologist and principal owner of Matthew J. Hill Consulting. Mario Moussa, Ph.D., is president of Moussa Consulting and the author of three books including The Art of Woo.