4 minutes

'Five finger consensus' allows all directors to weigh in on key decisions.

It seems that almost every credit union we’ve been working with lately has been struggling with the idea of consensus. They all seem to want it, most of them claim to be experts at coming to it, and yet few of them know what it really means.

One of our favorite facilitation techniques is what Michael Wilkinson calls “five finger consensus.” It goes like this: We’ll call a question, something like “Moving forward, XYZ Credit Union should charter a Governance and Nominations Committee.” Next, we charge the board members to vote their minds: “Hold up five fingers if you strongly agree that your credit union should charter a Governance and Nominations Committee; four if you agree; three if you can live with it; two if you disagree; and one finger if you strongly disagree.” (At this point, we’ll tell them to be mindful of which one finger they hold up, which is typically greeted with a round of laughter.)

Then, we’ll ask directors at either end of the spectrum—those who voted with one or two fingers or with five—to share their thoughts. After additional discussion, we’ll then re-call the question and the vote. Sometimes the vote will change, and sometimes it will remain the same, but in either instance, those who voted will have had the chance to express their thoughts, and if the threes, fours and fives are in the majority, then that decides the issue.

Is five-finger consensus a formal way to obtain a board vote, you ask? Usually not, but it is an engaging way to take the pulse of the room, ask for input and discussion, and then call a vote—all of which is consistent with building a broader consensus. Could you apply the same process to your board discussions and votes? Absolutely.

What is consensus? Merriam-Webster defines it as “a general agreement about something.” Consensus involves coming to an agreement to support a decision that is in the best interest of the whole. It affords everyone an opportunity to share their thoughts and opinions. Consensus, in the end, is a decision-making process informed by the shared wisdom of the group. It takes courage, humility and respect among all of the group’s members. It may require a measure of letting go for the greater good. Those who voted with only one or two fingers may be outvoted, and that has to be okay with them once they have had a chance to voice their concerns.

When we facilitated the five-finger consensus recently at a board retreat, one attendee, who was taking a minority position, said, “I’m satisfied. I just wanted to be able to have the conversation, and we’ve done that.” Sometimes, people just want to be heard.

Consensus doesn’t require unanimity. It isn’t talking through an issue again and again until 100% of you and your colleagues on the board are in agreement. Credit union boards are not held to the same standard as a jury in a criminal trial—come to a unanimous decision or end in a mistrial as a hung jury. If every director does not agree, that doesn’t mean a decision cannot be reached and the issue must be put on hold indefinitely. Consensus doesn’t mean you have to be ultra-polite, never disagree with your colleagues and vote accordingly just to get along.

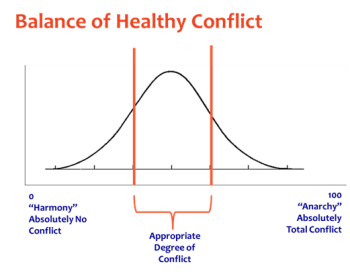

On the contrary, a measure of disagreement, in a respectful and appropriate way, is healthy for a board. In fact, we would be concerned if directors never disagreed. Boards that are in complete “harmony” and never experience conflict or disagreement are just as dysfunctional as those that experience complete “anarchy” and find themselves in total conflict.

On the contrary, a measure of disagreement, in a respectful and appropriate way, is healthy for a board. In fact, we would be concerned if directors never disagreed. Boards that are in complete “harmony” and never experience conflict or disagreement are just as dysfunctional as those that experience complete “anarchy” and find themselves in total conflict.

There should be an appropriate degree of conflict, or challenge, on your board, particularly when you are wrestling with difficult strategic issues. That’s why we have boards. It would be much easier (and more efficient) if a credit union were simply run by its CEO or a single trustee. But society is not built that way, and neither are our organizations. We value diverse thought and input. Our organizations are stronger because they rely on a system of checks and balances.

If you are not challenging each other—if there is no one on your board voting with one or two fingers and offering their thoughts along the way—what true value are you offering to your colleagues on the board, to the CEO and his or her management team—and ultimately to the members you represent? Just be sure to disagree in an agreeable way, and remember that the idea of consensus, as the Quakers would say, is ultimately about “unity, not unanimity.”

Michael Daigneault, CCD, is CEO of Quantum Governance L3C, Herndon, Virginia, CUES’ strategic provider for governance services. Daigneault has more than 30 years of experience in the field of governance, management, strategy, planning and facilitation, and served as an executive in residence at CUES Governance Leadership Institute. Jennie Boden serves as the firm’s managing director of strategic relationships and a senior consultant. She has 25 years of experience in the national nonprofit sector and served as the chief staff officer for two nonprofits before coming to Quantum Governance.